Of the large cities of the Yangtze Delta region perhaps the least visited is Nantong. Situated on the northern bank of the Yangtze River, not far from the mouth of this enormous river, Nantong is a modern city best known for its shipbuilding. Its shipyards are still a mainstay of the economy, as well as a number of other industries such as pharmaceuticals and agribusiness. Shipyards notwithstanding, this is not a city which appears on many tourist itineraries, and we were the only foreigner in sight for most of our stay. That doesn’t mean there is nothing to see in Nantong, however. Of the several tourist objects on offer, the most enticing is probably Wolf Mountain, and it was there that we headed first immediately upon arriving in the city.

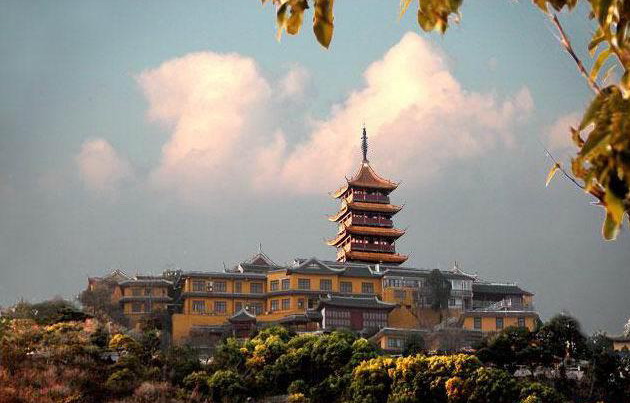

It was a sweltering mid-summer day when we made our way out to Wolf Hill. Karen, Cameron and I took a taxi from the Nantong bus terminal, having shown the driver the name of the hill (Lang Shan in Chinese) on a piece of paper. The drive through Nantong, a modern, Chinese boom-town took about ten minutes. Though at 106 metres Wolf Hill is not of any great height, the Jiangsu plain along the Yangtze River is very flat, with the result that you can see the temple from some distance. Topped by a multi-storeyed pagoda, it is easily the most interesting feature of the landscape around Nantong.

The taxi dropped us at the foot of the hill, a rocky protuberance rising up above the strip of concrete shops in that far-flung suburb of Nantong. As soon as we got out of the taxi you could hear the roar of cicadas in the trees. For us it reminded us of summer in Australia in our childhoods. Chinese domestic tourists were noticeable by their absence; there wasn’t a single tour bus in the vicinity, and there was no one waiting outside the entrance gates either. Perhaps the summer temperatures had discouraged local sightseers.

We went up to the ticket-office and found that the entrance price was now 50 yuan, which was less than we had been led to believe. Reading more into it than we possibly should have, we speculated that it might have been the dearth of visitors which had prompted the climb-down in price. Ticket in hand, we entered the site, unsure of whether to go left or right. Ahead of us was a the sheer rocky outcrop, with water pooled around it’s base; we clearly couldn’t go that way. Heading right, we came to the bottom terminus of the cable-car. The woman told us that it was a further 40 yuan to ride the cable-car; as often happens in China, it wasn’t included in the entrance price. Not wanting to pay that much, we decided to walk up the hill in the head instead.

Heading back the way we had came, we encountered a few minor monuments around the base of the hill. There was one wooden hall with old timber beams that had the look of being centuries old. Further along, there was a ornate, stone gateway with some stone tombs beyond. These tombs, marked by upright stelae, belonged to revered Chinese poets going back as far as the Tang Dynasty, one thousand years before. Even if you have no idea about Chinese poetry, they are attractive enough examples of traditional design to be worth a quick peep, but they are not the main attraction. Having come that far, the main thing is just to start up the stairway, which leads from there to the temple atop Wolf Hill. Even if you have no idea about Chinese poetry, they are attractive enough examples of traditional design to be worth a quick peep, but they are not the main attraction. Having come that far, the main thing is just to start up the stairway, which leads from there to the temple atop Wolf Hill.

A ten to fifteen minute climb up a steep flight of stairs will bring you all the way to the top of Wolf Mountain. Partway up there is a side path which leads you to the River-Watching Pavilion. It is a pleasant enough diversion, but the views of the Yangtze are far better from the top. We would recommend going straight up and only visiting the River-Viewing Pavilion on the way back down if you haven’t head enough of the sight-seeing yet. Another option is perhaps more worthwhile; it leads to a small temple to the left of the main path, and the relics here include a Ming Dynasty brick pagoda, which appeared to be on a slight lean. Beyond it, through various gateways, is a small wooden building painted in red, with a series of small garden-courtyards inside.

Along the main path there are a few businesses selling cold drinks as well as religious-themed souvenirs such as amulets and prayer beads, but there is little reason to stop excpt for thirst. Just before the final flight of stairs, there is a small pavilion which is of more interest. Though just another Chinese pavilion in most respects, it has a unique motif near the corners of a sea-monster with an open maw. This was a reminder of the fact that this temple had long been favoured by sailors about to go on long sea-voyages. A famous monk who had once resided here was credited with the ability to protect seafarers from the monsters of the deep.

At the top you will receive a panoramic view of the Yangtze River, which is perhaps the best thing about this hill. Down along the Yangtze shoreline are Nantong’s famous shipyards, still the most celebrated of the town’s industries. But it was the vast sweep of the Yangtze River itself, the third longest river in the world, which is most impressive. Nantong is the last major city on the banks of the Yangtze before it finally enters the sea. The Yangtze here is very broad- you certainly can’t see the far side- and it is certainly a good place to get a view of the river that has been so crucial in the history of China.

Then up a short, steep flight of stairs is the main temple. The gateway is a colorful mix of yellow walls, postal-red door-frames and crossbeams and a black-tiled roof with glazed, porcelain tiles for ornamentation. Again a sea-monster motif was in evidence, adding to the local charm of the shrine. A second flight of stairs will lead you up another wooden hall, just one of a series of buildings rambling over the crest of the hill. This one had statues of colorful Buddhist deities in glass cabinets and a gold-painted statue of Guilin, a goddess of compassion. Off to the side are various monastic buildings including a vegetarian kitchen, but these seemed to be closed to casual visitors. Instead there is another terrace out the side, which affords more views of the surrounding plain.

On the way back down we finally stopped at the River-Viewing Pavilion and bought some bottles of water off the drinks vendor who made a lonely living there; the whole time we were sitting there, no one else appeared. For us, it was enough to sit surrounded by trees and the sound of birds and cicadas, a rare treat in the industrial heartland of Jiangsu. Though we all agreed that the charms of Wolf Mountain were somewhat modest, we thought it was worth a couple of hours of our time, and were certainly in no hurry to get back to the bustle of Shanghai.